⏰ Tik-Tok, DSA O'Clock?

💡 Summary

- Background: On Feb 19, EU Commission opened proceedings against TikTok, investigating potential breaches of Digital Services Act (DSA) related to ad repositories. We can confirm that there are several issues.

- Ad Library Features: TikTok's ad library, although compliant from afar, has some problems, including delays with showing data, lack of details for some ad types, and limited search parameters, which are hindering effective researcher use.

- Incompleteness & Reliability Issues: The ad library lacks vital details on ad content, e.g., product information and subject matter, impeding comprehensive analysis. The platform struggles to keep pace with evolving features, impacting the library's reliability.

- Deleted Ads & API Limitations: Slow removal of ads and API issues (e.g., missing context information) pose challenges. 206 ads were removed based on DSA reports, only 9.9% of removals were identified through automated means, a stark difference compared to the highly automated content moderation approach of TikTok.

- Commercial Communication Challenges: TikTok's "other commercial content" section lacks essential details, making it almost useless for researchers. Users' limited use, sometimes misuse, of disclosure functionalities and missing product information produce mainly data waste.

By Alexander Hohlfeld, Anna Semenova, Martin Degeling, Greta Hess and Kathy Meßmer.

On the 19th of February the European Commission opened formal proceedings against TikTok to assess whether the platform breached the Digital Services Act (DSA) in several areas, including “[t]he compliance with DSA obligations to provide a searchable and reliable repository for advertisements presented on TikTok”.

The background: According to the Digital Services Act, “Very large online platforms or very large online search engines should ensure public access to repositories of advertisements presented on their online interfaces to facilitate supervision and research into emerging risks brought about by the distribution of advertising online” (Recital 95, which provides details on the mandatory ad archives for VLOPs from Article 39).

As civil society researchers using TikTok’s ad library to assess risks - see our post from last week - we have also checked compliance of said library with the requirements for advertising repositories set out in Article 39 of the DSA. In the following, we want to provide a short overview of what TikTok’s ad library does and does not offer.

Different types of advertisements

The DSA differentiates between “advertisements” and “commercial communication”. To be considered as an ad, the DSA sets the requirement that the platform (TikTok in this case) has to receive remuneration for promoting the ad:

Article 3: Definitions

(r) ‘advertisement’ means information designed to promote the message of a legal or natural person, irrespective of whether to achieve commercial or non-commercial purposes, and presented by an online platform on its online interface against remuneration specifically for promoting that information;

For the definition of commercial communication, the DSA refers to Directive 2000/ 31/EC:

Article 2: Definitions

(f) “commercial communication”: any form of communication designed to promote, directly or indirectly, the goods, services or image of a company, organisation or person pursuing a commercial, industrial or craft activity or exercising a regulated profession. The following do not in themselves constitute commercial communications:

- information allowing direct access to the activity of the company, organisation or person, in particular a domain name or an electronic-mail address,

- communications relating to the goods, services or image of the company, organisation or person compiled in an independent manner, particularly when this is without financial consideration;

Both must be disclosed in the ad repository, which TikTok formally fulfills. Advertisements can be found here: https://library.tiktok.com/ads; commercial communication can be found here: https://library.tiktok.com/other-commercial-content.

Let’s take a look at how the ad library makes this content available.

1. Advertisements

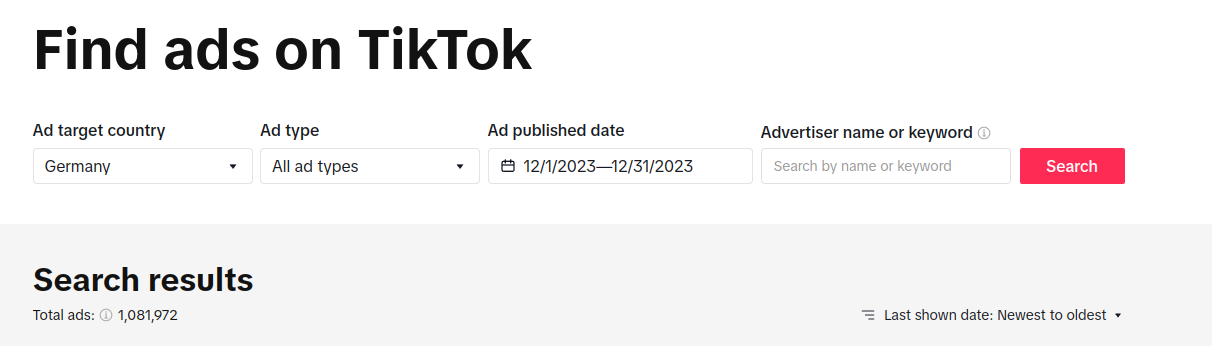

TikTok offers, as required in the DSA (Art. 39), a “searchable” tool that “allows multicriteria queries”. The “multicriteria” search allows to filter for:

- Ad target country

- Ad type

- Ad published date

- Advertiser name or keyword

The ad target country can be filtered by any European country, and limiting the search to a specific time period through “ad published date” works fine as well. However, the ad type category only offers the option “all ads” and does not allow differentiation between different types of ads that we know exist on the platform. Finally, the interface provides a search box where one can enter search terms and either select autocomplete suggestions (e.g., for advertiser names) or use the “keyword” as a generic search term. This design decision, along with the underlying data, keeps the ad library from being a useful tool for researchers.

Take the following use case as an example. If you used TikTok in Germany in January, you have likely seen the ad below: An ad by the lollypop brand “Chupa Chups” featuring the (in Germany) well-known musician Nina Chuba. If you would be interested in understanding more about this ad campaign on the ad library, you would probably have started by filtering ads by typing “Chupa Chups” in the search field.

TikTok then suggests “CHUPA CHUPS” as an advertiser name, but there are no ads associated with this advertiser. Similarly, information from the description and search terms like “Nina Chuba”, “chupachups.de,” or “foreverfun” will either bring up nothing or content that seems randomly selected. The results also differ depending on how you put the search terms in quotes: Whether you add the quotation marks yourself or select the quoted suggestion will produce different results.

What actually helps to find the ad is knowing who paid for it. In this case: “CFP Brands Süßwarenhandels GmbH & Co. KG”. Experienced users have the option to access this information by clicking on the “share” menu within the app when they come across the ad. However, if you try to locate the ad by searching through your watch history after recalling seeing it, you’ll only find the original video content, not the ad itself. Therefore, the advertiser details won’t be available through this method.

While TikTok complies with the legal requirements for offering a “multicriteria search” as such, this search does not make it easier for researchers to find specific ads. It took us a while to find the specific “Chupa Chups” ad.

Searching with broader criteria, e.g. with the purpose of finding political ads, often results in a very large number of unrelated ads with no information about why a specific ad appears in the search results.

Incompleteness & Lack of Reliability

We have already discovered unenforced advertising guidelines through TikTok’s ad library (e.g., with political ads or ads to minors). However, we would still want to emphasize that the ad library falls short in providing robust tools for researchers.

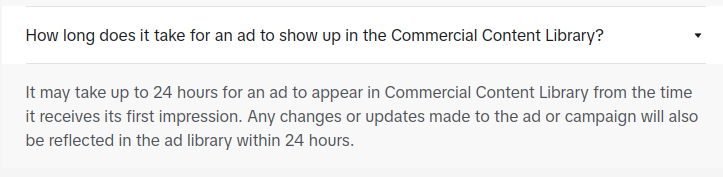

Although TikTok claims that ads would appear within 24 hours after their first impression, we figured out that a small number of ads appear in the ad library way later.

On 11.02.2024, we were able to find 36,150 ads that had their first impressions on February 8th and 9th. That means they appeared in the ad library within a 48-hour timeframe. At the time of writing, 37,240 (+1,090 or +3%) additional ads are listed, and the numbers are still increasing daily.

Missing information on ad content

According to the DSA (Art. 39(2)), the ad repositories should include information like, e.g., who the target groups are, when the advertisement was published and who paid for it. While TikTok checks most of the boxes, the first item on the list in DSA’s Article 39, which requires to provide information on “the content of the advertisement, including the name of the product, service or brand and the subject matter of the advertisement” (Art 39(2)a), is not provided.

The ad library shows the original video but no information on the product or the subject matter can be found. For example, there are no video descriptions, lists of used hashtags, or other information users see when using the platform. Any ad-specific information, like links to external websites users are directed to, is missing as well. TikTok identifies each ad by a unique ad-ID in the library. Still, it is not possible to find the original video on TikTok because there is no link between the ad-ID and the regular TikTok video-ID. It is also not possible to go the other way around and find an ad based on the original video-ID.

It is striking that the search seems to cover at least some of the video-related information, but it is not listed in the ad-details. For example, the search for “Nina Chuba” does not list any ads in which the artist appears as an actor (or her name is mentioned in the description), but thousands of ads in which the artist’s music is used - without this information being listed anywhere.

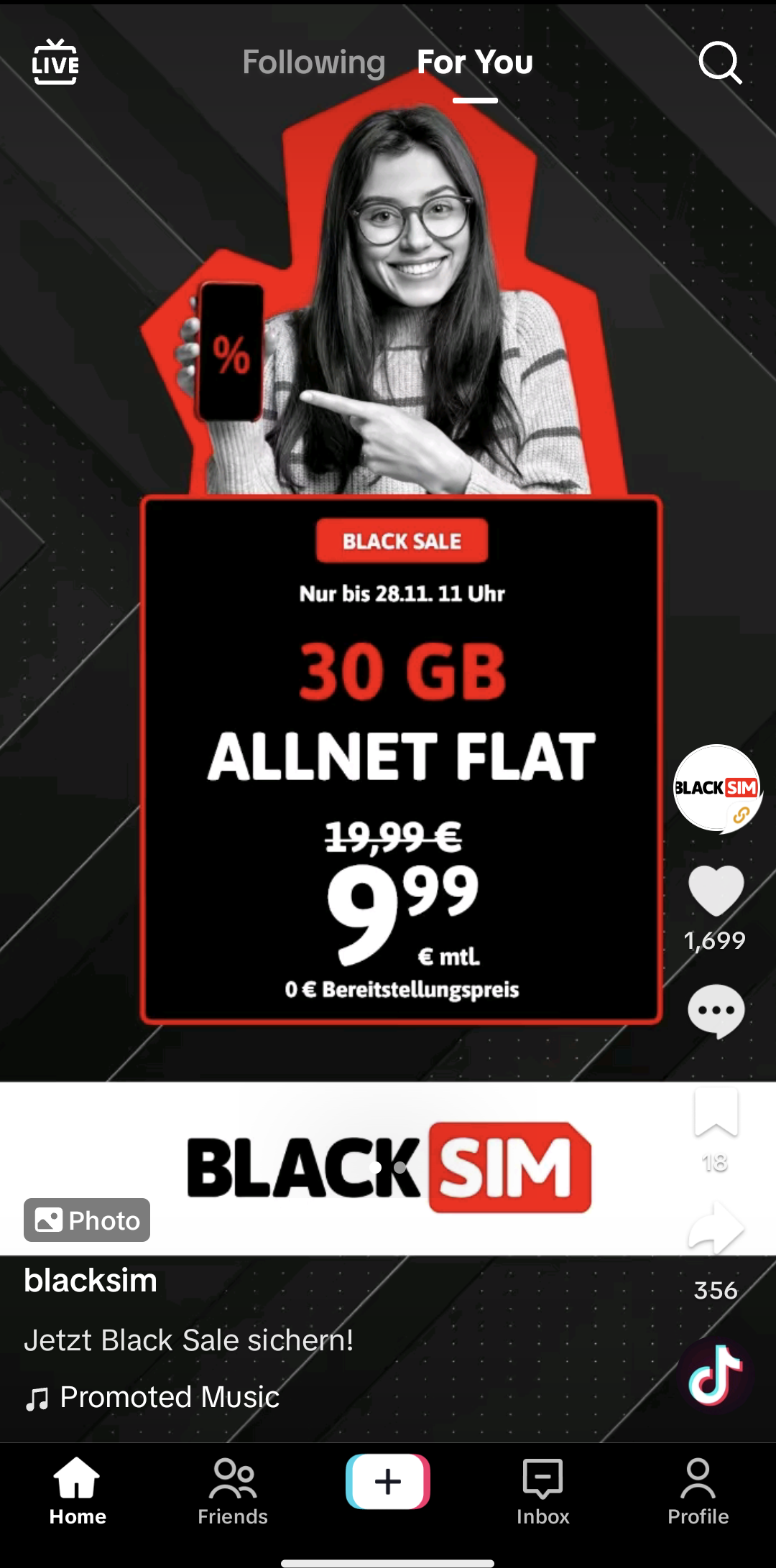

Delving deeper into our dataset, we found that the ad library only shows the content for video-based ads, but not all ads are based on videos. For example, we observed 193 ads based on slideshows and 3 based on live content in our automated analysis of the For You feed. While slideshow ads are only listed with meta-information but without showing the advertised content (see example below), livestream ads don’t appear in the ad library at all.

This observation points to a significant challenge: tools like the ad library have difficulties keeping up with the constant introduction of new features and products for content monetization by platforms. Importantly, researchers face a tough task as they lack the proper tools to thoroughly check how up-to-date these repositories are. The repository does not offer any insights to determine if all the latest products are covered or if there are notable gaps in the ad library.

Missing differentiation on the reach of the ads

According to the DSA the ad library should contain “[t]he total number of recipients of the service reached and, where applicable, aggregate numbers broken down by Member State for the group or groups of recipients that the advertisement specifically targeted” (DSA, Art. 39 (2) g). TikTok’s ad reach information only includes broad ranges (such as 1K-10K, 1M-10M, 10M-20M) and specific numbers for countries (e.g., 219K), but lacks specific details on groups targeted by the advertisement. Consequently, assessing how many individuals from particular age groups in specific countries viewed the ad is challenging.

Information on deleted ads

In the cases where a platform “has removed or disabled access to a specific advertisement based on alleged illegality or incompatibility with its terms and conditions, the repository shall not include the information referred to in those points” (DSA, Art. 39(2)g). Based on our initial impression, TikTok seems to fulfill this requirement. The DSA specifies which information shall be included in such cases, like whether the decision was made on the use of automated means, references to the legal ground relied on (where the decision concerns allegedly illegal content) or a reference to the contractual ground relied on.

We created a dataset of 2,268,571 deleted ads (roughly 11.5% of all ads at the time) containing information on the rejections provided by TikTok. The most common ones were:

| Category of Reason | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Suspicious Activity | 1284519 | 56.62% |

| Prohibited Industry (of the targeted location) | 226819 | 10.00% |

| Expired authorization | 143048 | 6.31% |

| Targets wrong location | 101884 | 4.49% |

| Medical and Health | 89260 | 3.93% |

| Minor Protection | 62472 | 2.75% |

| Weight and Body Image | 57596 | 2.54% |

| Spark ads/Pangle | 51384 | 2.27% |

| Sexual Content | 42563 | 1.88% |

| Consumer Protection: Financial exploitation concerns | 38531 | 1.70% |

| …. | … | … |

Only a total number of 206 ads were removed based on a report under the Digital Services Act, according to the rejection information:

“We have removed your ad(s) because we have determined that they contain illegal content under European law. We have taken this decision based on a report under the EU Digital Services Act.”

A total of 205,582 ads, constituting 9.9% of all removed ads, contained indications that the violation was identified through “automated measures.” This is in stark contrast to the content moderation practices TikTok has on regular content. According to the DSA Transparency Database, 98% of the videos TikTok flags for removal or restrictions are identified automatically.

As the chart above shows and as we have shown in our previous blog post on ads “removing ads is slow and usually happens after ads have reached their audience”.

Unsatisfactory API

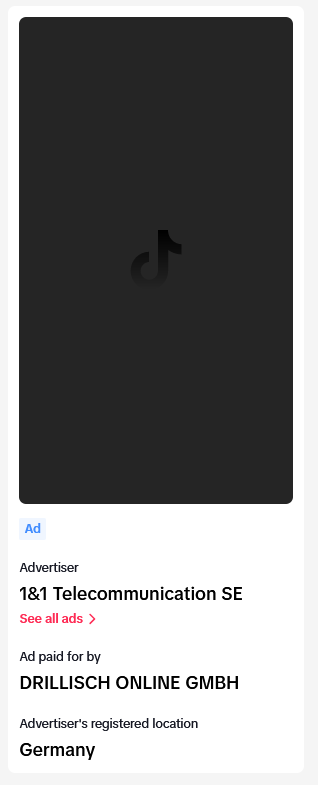

Besides the web version of the ad library, TikTok gives registered users access to the data through their Commercial Content API. With that access, developers can retrieve data in a more machine-readable format. Still, there are small differences that - depending on your research questions - make the website more informative. We have compared the data available through the API with not publicly documented data sources (also known as “hidden API”) made available through the ad library.

As you would expect, the difference is marginal as the numbers are all the same. However, there occasionally is one bit of information that makes the analysis easier when looking for more context on an ad or advertiser. The ad library website additionally shows the username of the TikTok user who published the original video (note: that is often a different account than the one paying for and placing the ad!). For example, in the case shown above, it will list the account name and additional details in the code. This information is not made available through the API, making links between ad campaigns and creators more difficult.

{"tt_user:

{

"username": "chupachupsde",

"display_name": "Chupa Chups Deutschland",

"avatar_url": "https://p16-sign-va.tiktokcdn.com/tos-maliva-avt-0068/xxxxx",

"follower_count": "217.5K",

"profile_web_link": "https://www.tiktok.com/share/user/7029742742520710149?source=ad_review",

"account_type": "BLUEV_BA"

}

}

Here is a note for those working with the Commercial Content API: The documentation is missing information. While the api lists the structure of the rejection_infoon the website, it is not documented how to query for this field. Developers need to add this field to their request to also get that info. E.g. https://open.tiktokapis.com/v2/research/adlib/ad/detail/?fields=ad.rejection_info

2. Commercial communication

Content on TikTok that can be considered as “commercial communication” according to the DSA, can be accessed via the sub-page “Other commercial content“ of TikTok’s ad library. Thereby TikTok differentiates between “Promotional content” and “Paid Partnership”.

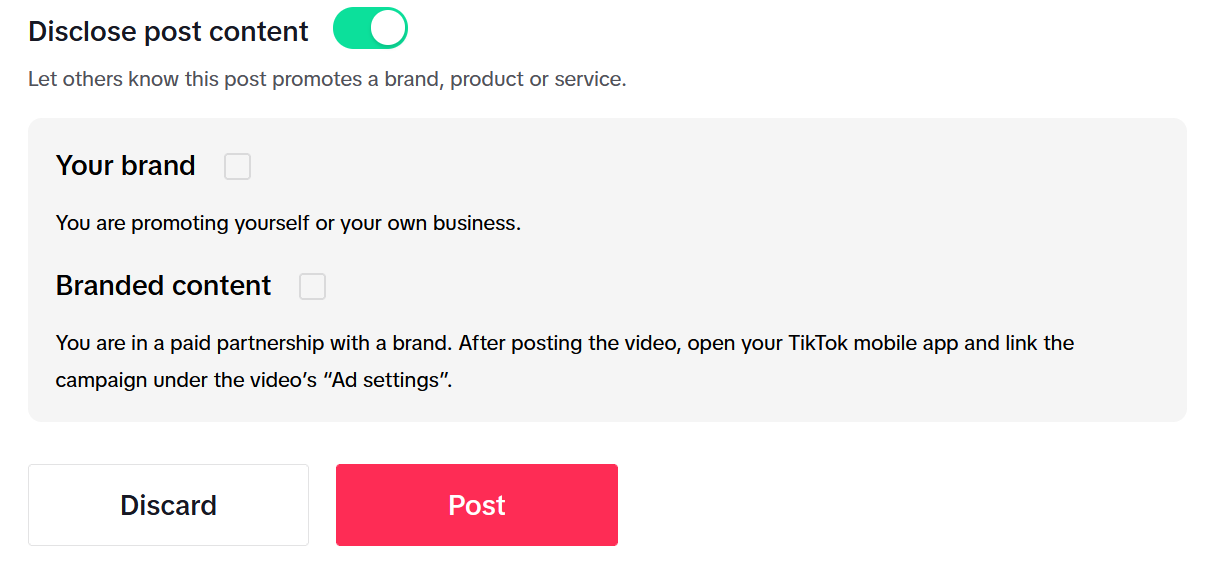

With this content, TikTok is not necessarily involved in the remuneration. Before uploading a video, users have the option to “disclose post content” and can choose whether they promote their own brand or branded content as part of a paid partnership. Promotion of own brands or businesses is then labeled as “promotional content” and branded content as “Paid partnership.” As we have shown in our analysis of ads, only a very small number of users use this functionality.

The library for “other commercial content” offers very little information. Only the account name, the brand name, a total estimate of video views and an embedding of the video can be accessed. While the brand name is unavailable for most videos, TikTok also does not offer any information about the product, the video description or a link to the video. For most videos, it is not at all clear which brands or interests are behind the content. TikTok also does not offer any identifier or link that researchers could use to save or share specific videos.

Quo Vadis TikTok Ad Library?

Our analysis shows that there is still a long way to go for TikTok’s ad library to become a reliable tool for users and researchers. While the ad library complies with some basic legal requirements, it does not provide necessary information about the content of ads. Moreover, the interface and nontransparent search functionality make it hard to use. The API offers even less information, and neither of the officially provided methods of accessing TikTok allows for aggregated analysis. The “Other commercial content” category on “commercial communication” can be considered almost useless due to a lack of information provided. The simultaneity of a massive misuse of the feature and a lack of serious use creates a huge amount of data waste which is impossible to study systematically. While elsewhere TikTok prides itself on its highly automated approach to content moderation, it does not seem to check these self-attached labels at all and does not even require an indication of the brand being advertised. Whether or not a video there contains or not contains commercial communication is in most cases impossible to tell. Overall, the TikTok ad library currently feels a lot more like the Wild West than a reliable tool that gives researchers systematic insight into the platform’s advertising ecosystem.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: