🛫 Auditing TikTok: Methodological reflections on the RSBA process

By Kathy Meßmer, Martin Degeling, Alexander Hohlfeld.

In February 2023, we published a framework for “Auditing Recommender Systems”. With reference to the Digital Services Act (DSA), we have outlined how risk assessments and algorithm audits of recommender systems of very large online platforms (VLOPs) should be conducted. Therefore, we proposed a risk-scenario-based audit process (RSBA).

But we didn’t just want to theorize; we also wanted to walk the talk and test our approach by auditing TikTok (which is designated as a VLOP under the DSA). Over the upcoming weeks, we will publish our findings here on the blog.

Before we do so, let us give you an overview of our findings and methodological decisions generated throughout Step 1 of the RSBA process.

As a quick recap, the RSBA process comprises the following 4 steps:

Select audit type or platform element:

Connected elements

While we initially described those 4 steps as consecutive, we learned quite quickly through our RSBA journey that this process needs to be iterative. For example, we recommended deciding on a systemic risk before starting the RSBA process. However, as an independent Civil Society Organisation conducting an external risk assessment, we discovered that certain risks only surfaced during the exploration phase, while others we anticipated were hindered by inaccessibility of data due to imposed restrictions. This realization underscores the intricate interplay between exploration, systemic risk identification, and the selection of appropriate measures. Navigating these steps iteratively becomes imperative to address the challenges inherent in external risk assessment comprehensively.

Step 1 - Plan

Step 1 of the RSBA process aims to obtain a deep understanding of the platform under scrutiny and identify stakeholders who should be involved in the audit process.

Understanding the platform

We have taken some time to understand TikTok as a platform and to plan the audit process as a whole. This phase took us much longer than expected.

We spent roughly 9 months exploring and understanding TikTok technically and sociologically by swiping, watching and playing around with different data collection options. We set up some experimental sock puppet accounts, started a scraping test run and tried to figure out how to replicate well-known investigations like that from the Wall Street Journal on depression rabbit holes and mental health. This experimental phase was accompanied by a research sprint, and we have already reached out to relevant stakeholders to discuss systemic risks, TikTok and its inner workings (see below).

Using the RSBA’s questions as a guiding framework, here are some things that we learned:

What type of media is the platform working with?

TikTok’s most important content type is short, entertaining video clips, from classic cat content and dance challenges to carpet cleaning videos (if you are interested in the trends of 2023, see TikTok’s overview - available for different countries). The mobile apps allow users to make, edit and upload these videos. Common and well-known features are a huge variety of filters, CapCut templates and the possibility to remix videos with audio snippets or other videos in duets. The videos are posted with additional descriptions and hashtags and can be published with subtitles. Although a duration of up to 10 minutes is possible, the average video is still short (around 35 seconds) because the platform logic favors that.

In recent years, TikTok LIVE has also gained significance for creators and contributed to TikTok’s revenue (see turnover data below). However, the majority of users’ time on the platform is still spent on the For You feed.

What is the audience?

TikTok is extremely popular among younger users. In a survey that we conducted as part of the RSBA process with young people between 18 and 25 in Germany, 59% stated that they use TikTok (for global statistics, see here). It has been reported that Gen Z (people born between 1996 and 2010) use the platform as a search engine and others have found that youth are using it as a trustworthy news source. At least in our own research, we cannot confirm the latter. In our survey, 70% said they do not find TikTok trustworthy (they trust YouTube, though). Still, more than half of our surveyed users use TikTok for information search. (Yes, this is a sneak peek into our data. More data and reflections on our methodology will follow. Stay posted.).

As these youth start shaping their understanding of the world through TikTok, the content they engage with and their relationship to the platform has far-reaching consequences for them as individuals but also for societies at large. Many of these consequences include systemic risks that fall under the umbrella of the DSA.

What is the platform’s main strategy?

In an internal document first published in 2021, the platform explains the rationale of TikTok’s recommendation algorithm (you can find the translated version on our GitHub page TikTok 101). That document describes TikTok’s main goal as increasing the number of daily active users and the time spent on the platform. To reach these objectives, the designers of the recommender system for the For you Page outline a number of “values”:

- Create value for the user: The “user value” is defined by TikTok as a short-term value, implemented in the algorithm, measured in time spent on the platform within a session (”keep them scrolling”), and as a long-term goal to ensure that users come back to the app (retention).

- Value for authors: Value for creators is defined as traffic to videos, interactions, income, etc., obtained by the creator.

- Platform value: TikTok generates the platform value through the algorithm based on factors like platform revenue, content security, brand effect and others.

- Indirect value: This is measured in metrics such as the notifications received by other users after commenting, as this may increase the retention of these users (”the user value of other users”), or the impact on the content ecosystem (”the author value of other authors”) and so on.

Just looking at the aforementioned Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), the developers reached their goals. In January 2024, TikTok has 15 million active users in Germany with an average watch time of 1h40min.

However, these KPIs are the goals defined for the recommender system. Of course, for the company employing the engineers working on those algorithms, increased usage is not a goal in itself. Bytedance, the company behind TikTok, is a for-profit organization with financial interests. Increasing the number of users and the time spent on TikTok allows Bytedance to steer more users toward the elements of the platform that drive profit.

When it comes to monetization, TikTok relies on various strategies. An official document from TikTok UK reports a turnover of $2,618,121,000 for 2022 (of which $1,485,861,000 is in the EU). Broken down by segments, at least in 2022, more than 60% of the turnover came from online advertising services, followed by the Livestreaming programme with 30%. Reports from 2023 suggest that this ratio might have changed over the last year. In 2023, TikTok was the first non-game app to reach 10 billion in consumer spending by selling coins to users with which they can tip content creators.

Besides that, TikTok is also expanding its shopping functionality (see Social Media Watch Blog from 19.09.2023, German Source).

As TikTok is not a publicly traded company, official financial reports with detailed and meaningful data are difficult to find and are only available sporadically. Similar to the algorithms of the recommender system, we can only make assumptions here about how the company works.

What technical elements are of interest?

As described above, TikTok has different features that might be managed internally by different product teams, meaning they might all behave differently and, therefore, may require separate algorithm audits.

For our RSBA process, we decided to concentrate on two of the platform’s technical elements: the For You feed and the search page.

In case you have never seen the mobile TikTok app at work, here is a short screencast:

-

For You feed: Regardless of the client the user is employing (Android, iOS, or web), TikTok’s most important product is the “For You” feed, also known within TikTok as #FYP (For You Page). This feature is mentioned in the Terms of Service as “a unique TikTok feature”, and when people talk about TikTok’s secret sauce, they usually refer to the algorithmic recommender system of this feature. It can be considered TikTok’s homepage and is the page where users spend the majority of their time on. This FYP is based on a recommender system that uses various behavioral metrics (we will elaborate further in an upcoming blog post; for now, see TikTok 101) to recommend videos for the user to watch. It shows a mixture of video clips, livestreams and ads - all seemingly related to the users’ interests.

-

Search Page: If you click on the search icon in the app (see video above), this leads you to TikTok’s search page. This page works with several forms of automated search suggestions, from which we are most interested in the following: A list of suggestions labeled “you may like”. Here TikTok suggests several topics you might want to search for. When you click on one of these suggestions, TikTok leads you to another page with search results (see video above).

Throughout our RSBA process, we discovered that TikTok is reworking this section constantly. In our data, we found evidence that TikTok is running A/B tests, and we observed that the interface and design were constantly changing.

When we started to approach this functionality, the suggestions in the “you may like” section were marked with red and grey bullet points. Additionally, some suggestions were labeled with a 🔥 icon. During our data collection phase, this icon was replaced by the 📈 icon. At least on the accounts we were working with.

While other people refer to the “you may like” section as “hot topics” or “trending topics”, we have a different stance here. Regardless of the marker, there seem to be three categories of these suggestions:

- Some refer to topics related to the recently watched video,

- some seem to be related to current events on the platform,

- and some seem to be related to current events outside of the platform or news headlines.

Little attention has been paid to this functionality and we did not find any descriptions of how it works, neither by TikTok itself nor by external researchers. However, there are clear indications that TikTok is generally working on its search function. Besides the changes we detected during our research, there were press releases announcing the integration of ads into the search and hints that TikTok is experimenting with third-party integrations, including a test run with Google.

While the decision to explore the #FYP’s recommender was due to its importance to the user experience, our interest in the “you may like” section was piqued by the irritating, sometimes clickbaity and sometimes weird search suggestions we found there. We will explain our decisions further in the related upcoming blog posts.

Identify and reach out to stakeholders

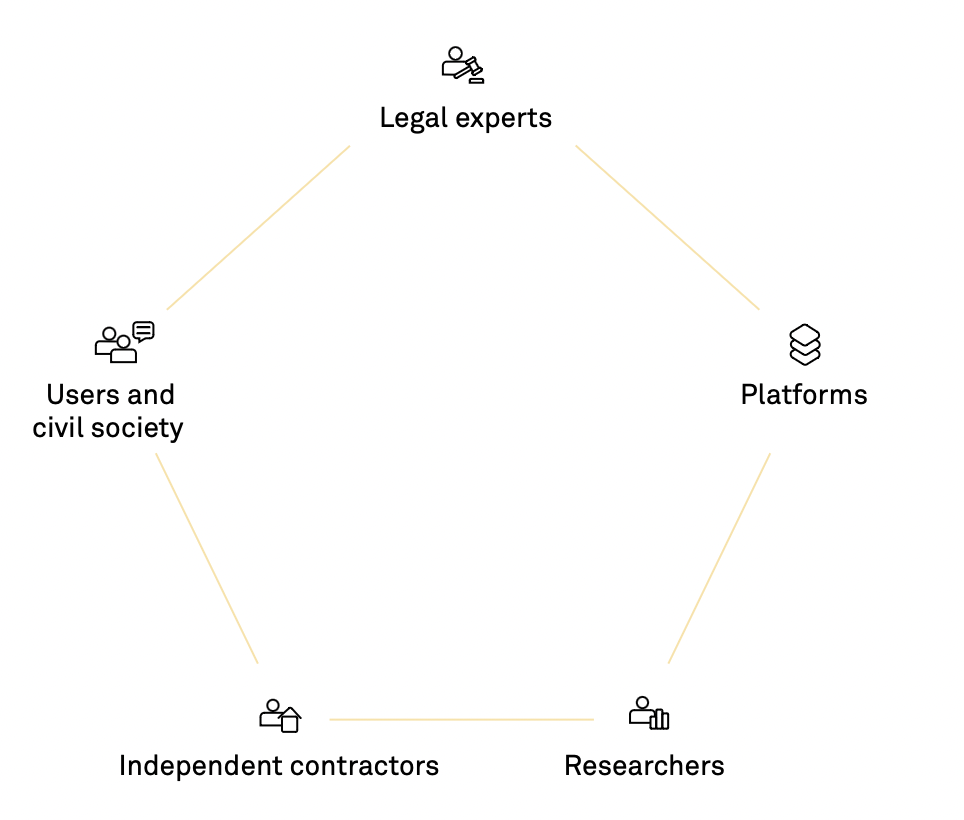

For the RSBA process, we identified 5 stakeholder groups that can potentially be involved.

For our TikTok Audit endeavor, we decided to engage with all five stakeholder groups throughout the process:

Platforms: Unsurprisingly, communication with the platform under scrutiny was reserved. Although we reached out several times and took part in some official workshops and webinars provided by TikTok, the platform did not seem interested in any sort of substantial exchange. We got access to the ad library API but have been informed that affiliation with a university or academic institution is required for access to the Research API.

Independent contractors: In Article 37, the DSA requires external compliance audits for very large online platforms. This can also encompass the auditing of risk assessments carried out internally by the platforms themselves. That is why we considered it to be helpful to involve independent contractors in the assessments and the audits of recommender systems because they bring specific audit expertise from other fields (e.g., finance, due diligence, etc.). Therefore, we reached out to several companies, which we guessed might become independent contractors at some point. During these exchanges, we learned a lot about the compliance audit business. As large auditors officially stated during the consultation on the draft delegated act on audits, one of their concerns is that the DSA does not provide clearly established criteria against which to assure. This goes hand in hand with the fear of having to define normative criteria and make normative decisions. That is why, in the end, we could not discuss our approach any further due to speaking completely different languages.

Legal experts: Legal experts were not among the stakeholders we contacted early on in the process. It was only when we started to set up the measurements that we started talking to consumer protection authorities and legal experts. These conversations helped us to reflect on our scenario definitions and the data setup. Beyond that, we learned more about specific harms to consumer protection stemming from platforms like Amazon or Temu.

Representatives of affected groups: When we started our RSBA process, we immediately reached out to the alliance of TikTok creators, Toca, but had to learn that it did not exist anymore. We also chatted with creators occasionally in workshops, but when we started to work on the specific risk scenarios, it became clear that our focus should be on all TikTok users of a younger age group. Therefore, the “affected group” under scrutiny became “TikTok users between the ages of 18 and 25”.

Users: Our main goal then was to learn as much as possible about the TikTok user group under 25. To make that possible and set up a proper and structured engagement process that goes beyond anecdotal evidence, we decided on doing focus groups. These focus groups have helped us understand the user journey and learn more about the risks that TikTok users themselves perceive on the platform. Our most important finding here was how much the younger generation is concerned about how content and advertisements on TikTok negatively influence the users’ self-image. Therefore, we decided to develop one risk scenario on that specific topic.

Researchers: Since we wanted to have the users’ perspective integrated into our risk assessment and also focus on societal implications, we decided to work together with a specialized research institute. Our partner for the aforementioned focus groups as well as the survey part of our RSBA process, was pollytix, a research company experienced in social and political sciences.

Civil Society Researchers: Although in theory, CSO and researchers are separate stakeholder groups, we noticed a large overlap in our stakeholder engagement. Besides journalistic investigations, it was primarily other civil society organizations that had also begun to examine TikTok closely and were open to exchanging knowledge and experience respectively. Therefore, we reflected on every step of our journey with different CSOs, their researchers and computer and data scientists. In the end, we decided to work together with AI Forensics, an organization experienced in adversarial audits of recommender systems.

Together with AI Forensics and pollytix, we developed the scenarios and opted for specific data collection methods (see following blog posts on Steps 2 and 3 coming soon).

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: